“Every border implies the violence of its maintenance.”

Ayesha A. Siddiqi

Monitoring and controlling the flow of people around the world, borders also serve to filter the rights they can access. In the context of late-stage capitalism and right-wing regression, border regimes prioritise profit over people and collectively punish those who are considered to be the wrong kind of ‘foreign’ – particularly those who are already structurally marginalised – via an intricate web of intersecting threats.

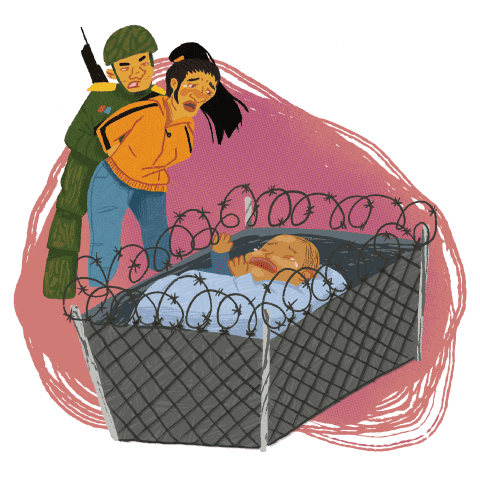

An absence of documents can perpetuate gender-based violence in myriad ways, not only for migrants and stateless people who may be undocumented, but also for citizens whose identities do not fit the narrow parameters set by national bureaucracies. The absence of safe asylum or migration routes coupled with harmful policies masked as ‘anti-trafficking’ measures is a source of immense hardship and violence. Discriminatory visa practices hinder and exclude Global South travellers and migrants, inhibit their rights to family life, education, and marriage, and engender exploitative conditions for workers. People who are disenfranchised and/or stateless are exiled and face detention and violence at the hands of states and border enforcement regimes.

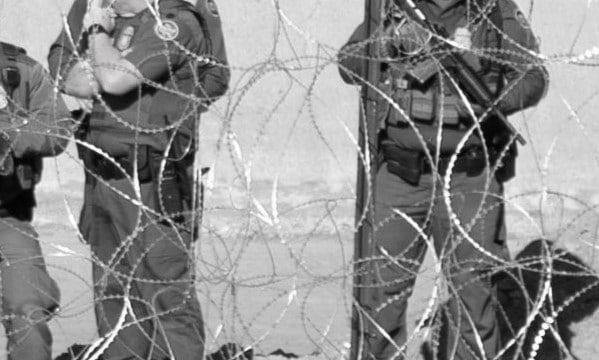

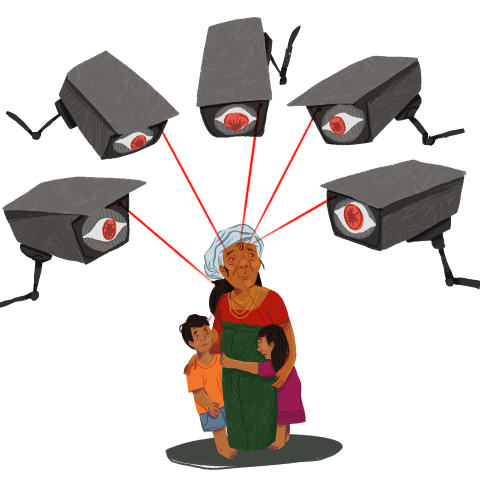

Mistreatment and abuse of people who are on the move or crossing borders is an extension of the same punitive approach wielded by states against citizens who are deemed criminal, contaminated, and/or unwanted. This is the same thinking that turns to prisons as a default response to crime, and that looks to police, rather than to empowerment of communities, for solutions to problems. The regressive portrayal of migration as a security issue has also created a lucrative business opportunity for violent interventions. Corporations profit from border regimes in multiple ways, with private firms handling outsourced visa processing, running detention centres and overseeing physical deportations. Collaborations between tech companies and border agencies enhance the surveillance tools used against people on the move. Although wealthy states’ outsourcing of border controls has resulted in far-reaching human rights violations, it has become a feature of aid conditionality for developing countries. Militarised borders demarcating occupied territories are sites of large-scale violence and deprivation of human rights. Carceral regimes even permeate migrant worker programmes, whereby confiscation of workers’ documents secures their captivity in their place of employment for as long as their labour is deemed useful.

Citizenship, as described by Hannah Arendt, is a prerequisite for ‘the right to have rights’. Non-citizens, therefore, are structurally deprived of many rights, such as the right to equal protection before the law; the right to work, and to equal pay for equal work; the right to education; the right to healthcare, including gender-affirming healthcare; the right to freely practise their religion; the right to a family life; and the rights to freedom of assembly, association and expression. Gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, ethnicity and nationality are among the factors which further disrupt non-citizens’ access to rights. Gender-based discrimination is perpetuated through restrictions on family migration/reunification, relationships, marriage or pregnancy (all of which may be reclassified as privileges which are only to be granted if earning above a certain threshold). Ableist health requirements for visas and citizenship discriminate against those living with HIV, disabilities, and long-term health conditions.